by

Abdulmesih BarAbraham, MSc.

Chairman

Board of Trustees

Mor Afrem Foundation

“I have more memories than if I were a thousand years old.“

Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867)

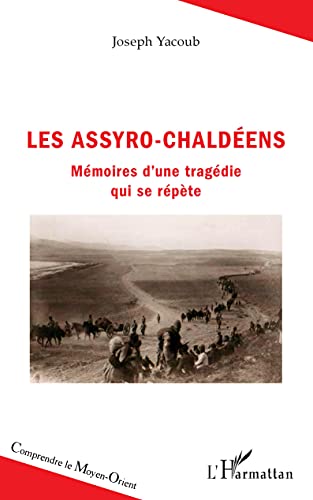

In his recent French book entitled “Les Assyro-Chaldéens : mémoire d’une tragédie qui se répète“ (The Assyro-Chaldeans: Memory of a Repeating Tragedy) and published in April 2021 by L‘Harmattan, Paris, Professor Joseph Yacoub describes a unique chain of tragedies of the Assyro-Chaldeans which culminated in the genocide of 1915-1918, known as „Years of the Sword.“

Joseph Yacoub is an Assyrian born in Hassake, Syria. He is Honorary Professor (Political Science) from the Catholic University of Lyon and was the first chair holder of UNESCO’s ‘Memory, cultures and interculturality’, expert on minority issues, human rights and Eastern Christianity. His parents, originally from Iranian Azerbaijan (Salamas district), suffered during the Turkish genocide of Assyrians during World War I, taking refuge in the Caucasus (Georgia) before settling in Syria in 1921. Prof. Yacoub is author of several books [1], some translated into English.

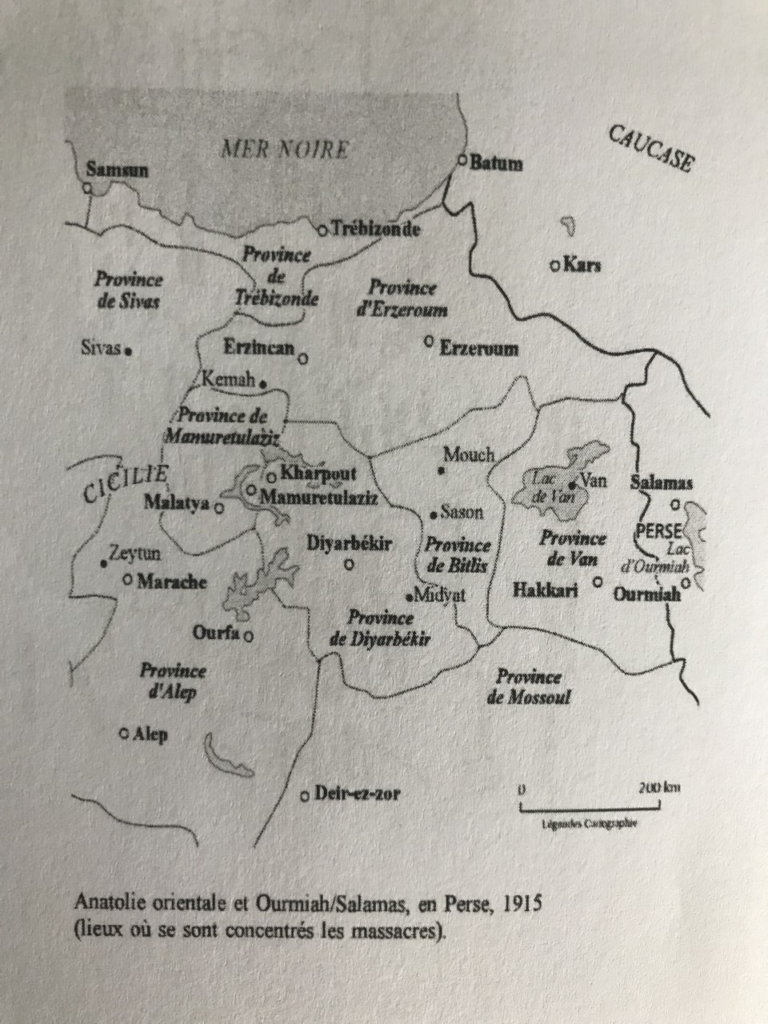

According to the author, the events of 1915-18 were „a hellish and masterminded undertaking, decided at the highest level of the Ottoman State to eradicate the Christians of the Empire. Systematic deportations and massacres took place over a wide area inhabited dominantly by Assyrians and Armenians stretching from Cilicia to Eastern Anatolia, as well as to Persian Azerbaijan.“

The book appears after several country parliaments, including Pope Francis, in 2015 and thereafter, recognized the 1915 genocide against the Armenians, Assyrians, and Pontic Greeks of Anatolia by the late Ottoman Empire [2]. Initiatives continue world-wide to erect memorial plaques and monuments where Assyro-Chaldeans live, with particular visibility in the Western diaspora (Europa, US and Australia). As the field of genocide research is widening and increasingly new sources are appearing, the academic journals, and the media is paying attention to the faith of the Assyrians.

The book cover states that convoys of deportees – and corpses – lined the roads to Mardin, Diyarbekir, Kharput, Sheikhan, Severek, Urfa, Ras-ul-Ain, Deir ez-Zor and Sinjar. As indicated above, the author‘s grandparents became victim to the exodus imposed on the community too. Hundreds of thousand people were killed. The physical genocide was accompanied by the dispossession of Assyrian land and property, as well as destruction of their cultural and religious heritage, both tangible and intangible. Historical monuments, schools, churches and monasteries were destroyed and left abandoned. Libraries containing rare books and rich manuscripts were devastated,“ the description continues.

With the title of the book emphasizing a „repeated tragedy”, Prof. Yacoub makes also a reference to previous massacres and the current existential tragedy of Christians in Syria and Iraq who are suffering since decades and reviving the memory of the great catastrophe of the past, known as „Sayfo“ (The Sword).

The book with its 280 pages is structured into thirteen chapters subdivided into multiple subsections, a conclusion, bibliography, while a few maps are included. As an introduction, chapter one (pp. 9-44) describes specifics of the Assyro-Chaldean tragedy and how this determined the destiny of the people in focus. In addition, the section sets the historical context of the existence of the Assyrians in Mesopotamia, which ties up to 612 B.C., the fall of the Assyrian capital Nineveh.

Chapter two (45-60) elaborates on the Syro-Mesopotamian region as a permanent war zone; Prof. Yacoub touches on the cultural domination and persecutions of the Greeks and Romans. He briefly outlines the early Christianization during the Partian era, while giving examples of the persecution under the Sassanids and Byzantium which were followed by the devastation of the Tatars, Mongols and Tamerlane, concluding with the oppression during the Ottoman era.

Chapter three (61-84) is titled „the spatial and temporal framework of the facts beginning of the 20th century,“ discussing the geopolitical situation in the north and north-eastern regions of Anatolia and Caucasus where Assyro-Chaldeans lived. The author emphasizes the structural weakness of the state and chronic instability of Iran/Persia as a state, explaining its conflict with the Ottoman Empire. He elaborates on the Anglo-Russian agreement of 1907 to conclude the chapter with an outline of the Adana massacres of 1909 during the reign of the Young Turks (known as Committee of Union and Progress), the Balkan war and their impact on the situation of the Christians in the Ottoman Empire.

Chapter four (85-98) discusses precursory massacres in Persia and the Ottoman Empire as prelude to the looming great catastrophe which broke out 1915, with references to Surma Khanum‘s Diary, the sister of Mar Shimun XXI (1887-1918), the Patriarch of the Church of the East who was killed in an ambush after leaving a meeting with the Kurdish leader Ismael Agha (Simko) at Kohnashahr near Dilman (in the Salamas plain north of Urmia). The situation in the empire and the hatred towards Christians was heated up by the Ottoman‘s proclamation of Jihad against the „infidels“ in November 1914 which, despite its obvious catastrophic consequences, Turkish historiography still interprets as an action not directed against the non-Muslim communities in the Ottoman Empire [3].

In chapter five (99-136) Prof. Yacoub treats the key topic of the calamities of 1915 in the Empire and the ordeal of the Assyro-Chaldean villages in the Van Sandjak and in Persia. The British Blue Book which he references here contained in its original version almost 100 pages on the Assyrian situation. Additional primary sources the author utilizes are from David Ilyan, Paul Béro, Abdelmassih Qarabashi, Jacques Manna and Israel Audo, the latter two being both eyewitness of the events in Van and Mardin respectively. This chapter covers also massacres and description of convoys of deportees from Diyarbekir, Mardin and Kharput during May and June 1915.

The events that followed the major tragedy in 1915 are treated in chapter six (137-168) which the author calls „The 3rd Act,“ unfolded in 1917-18 in the Turkish-Persian front, in Urmia, Azerbaijan, and Khosrawa. They resulted in the forced exodus of tens of thousands of Assyro-Chaldeans from Urmia to Iraq in July 1918. Here too, Prof. Yacoub refers to rarely utilized French sources such as the Lazarists and the Daughters of Charity, Sister Marie de Lapeyrière, and Pierre Franssen, who witnessed the massacres.

Chapter seven (169-188) discusses an interesting aspect related to the reception of the tragedy in Assyro-Chaldean memorial literature including classic Syriac sources, certainly a new aspect as it covers also complaints and lamentations describing exodus and disaster in locations such as Hakkari, Bashkale and Mardin. Furthermore, the witnesses have produced also ethical, moral, and theological reflections on the events.

As one of the best connoisseurs of diplomatic and military archives of France and Vatican, the author enriched the book with the chapters eight (189-204), nine (205-212), and ten (205-212) as they broaden Assyrian genocide research. Prof. Yacoub discusses in these subsequent chapters the role of French diplomacy as related to the Assyro-Chaldeans, the French Catholic Church‘s denouncing the massacres, and the Holy See‘s diplomatic and humanitarian role while referring to documents from related archives. The Vatican documents, particularly those from the pontificate of Pope Benedict XV, contain invaluable information about the events of 1915-1918.

The Assyro-Chaldean‘s efforts at the Peace Conference of Paris (1919-1920) are summarized in a short chapter eleven (219-226), while giving an overview of related publications and claims raised for autonomy in the south-eastern region of Anatolia.

Another short chapter twelve (227-232) summarizes the German parliament (Bundestag) recognition of the genocide of 1915 on June 2, 2016. The importance of this overdue recognition is that the German Empire was the key military ally of the Ottoman Empire during World War I.

In its main part, the German resolution explicitly acknowledges that Assyrians (also referred to as Syriacs, Chaldeans or Aramaic-speaking Christians) were affected by the deportations and massacres along with Armenians.

In

a final chapter thirteen (233-260) Prof. Yacoub provides

philosophical, political and moral reflections on the genocide, such

as a theological interpretation, thoughts related to responsibility

of the belligerents (Turkey, the Kurds, Germany, Persia, and

England), and punishment, He also touches on needed future education

on the genocide and on aspects of forgiveness by the victims.

Prof. Yacoub has succeeded in making an important and comprehensive contribution to the Assyrian genocide studies by covering the events related to the suffering of the Assyrians in their large spatial and temporal dimensions: from Adana to Hakkari and from Urmia, Azerbaijan to Mosul. In addition he has covered the pre-genocide developments that led to the catastrophe while providing new and important sources. He also covered the post-genocide diplomacy and novel aspects of philosophical, political and moral considerations along with the role of French diplomacy, the view of the French Catholic Church and the diplomatic actions of the Holy See.

As the author points out in his introduction, the tragedy described here goes beyond the national boundaries of the Assyrians and takes on other dimensions, questioning values of philosophy, politics, and religion, including morality. It makes us „think about evil and the meaning of history, the responsibility of the warring parties, the influence of the Bible, law and violence, justice and truth, political regimes and democracy, the great powers versus the small nations and the reason for wars,“ states Yacoub.

Abraham Yohannan (1853-1925), an Assyrian who was a professor at Columbia University in New York and author of “The Death of a Nation or the Eternal Persecuted Christian Assyrians,” is cited describing the events of 1915 in Persia and Turkey as „shameful and terrible pages in the revealed history of mankind.“

Prof. Yacoub‘s book is easy to read and nuanced even for non-experts. It is essential reading for those engaged in the study and research of genocide, provides important threads for further research and worth to be translated into English to reach broader audience.

Notes:

[1] Selected Book of Prof. Joseph Yacoub

LE MOYEN-ORIENT SYRIAQUE. La face méconnue des Chrétiens d’Orient, Salvator, 2019

Year

of the Sword: The Assyrian Christian Genocide, a History,

Oxforf

Press, 2016

Les

assyro-chaldéens du Causase (with Claire Yacoub),

CERF

EDITIONS ´, 2015

Qui

s’en souviendra?: 1915 : le génocide assyro-chaldéo-syriaque,

CERF, 2014

[2] According to list by the Assyrian International News Agency, a dozen of country parliaments has recognized the Assyrian Genocide; see: http://www.aina.org/genocide100.html,

[3] Abdulmesih BarAbraham (2017). „Turkey’s Key Arguments in Denying the Assyrian Genocide,“ in David Gaunt, Naures Atto and Soner O. Barthoma (Eds.), Let Them Not Return: Sayfo – The Genocide Against the Assyrian, Syriac, and Chaldean Christians in the Ottoman Empire, New York: Berghahn Book, pp. 219-232, DOI:10.2307/j.ctvw049wf.16